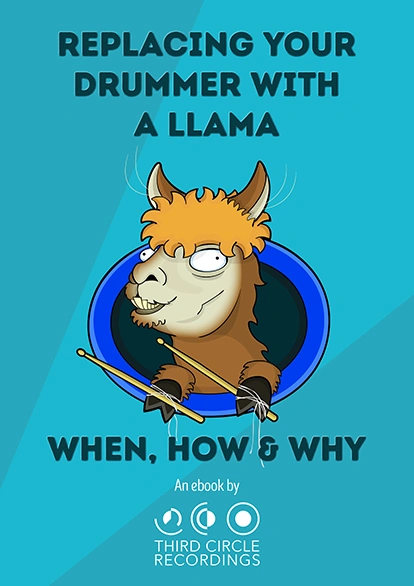

Recording drums in a small room is a problem that any engineer not blessed with an infinite budget must deal with at some point. Among the difficulties inherent in this scenario is the problem of comb filtering in the audio signal due to the microphone’s proximity to a boundary, i.e. the ceiling or a nearby wall. For example, if a singer sang into an omni-directional microphone placed 1 metre from a reflective wall or surface, the sound of their voice would hit the mic but also carry on past it, hit the wall, rebounding back and re-entering the mic about 6 milliseconds after the direct signal.

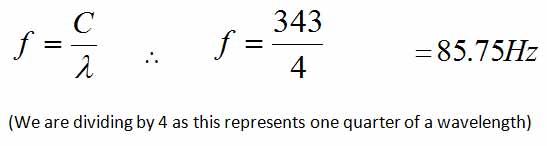

This is exactly the right amount of time for the frequency components around 85-86Hz to come back close to 180° out of phase with the direct signal. There will not be total cancellation, since the rebounded signal will be weaker and because the sonic characteristics of the singer’s voice are constantly changing, but the effect may still be significant.

Rounding down to 85Hz, at 170Hz the reflection will come back in phase and reinforce the 170Hz components within the direct signal. At 255Hz it will be out of phase again, and at 425Hz and 595Hz, and at intervals of 170Hz all the way up the frequency spectrum. This is known as “comb filtering”, due to the regular series of peaks and notches across the spectrum. It sounds phasey and generally undesirable.

This effect is demonstrated in this video, where a drum overhead microphone is moved towards a nearby boundary and back again. The comb filtering artefacts are clearly audible in the recorded signal. The first microphone – a Royer R121 ribbon mic – clearly suffers from this effect with great prominence given it’s bi-directional polar pattern, and thus greater susceptibility to rear reflections. The second mic – an Audio Technica ATM450 – reveals itself to be less harshly affected due to its cardioid polar pattern. This then demonstrates the importance of microphone selection with regard to its placement within a recording environment, as well as the importance of placing the mic as far from boundaries as possible, or, when this is not feasible, treating nearby surfaces with good quality acoustic absorption in order to eliminate as many reflections as possible. A combination of absorption and diffusion is most effective.