In the modern era of music recording it is generally accepted practice to use a click track as the basis upon which to construct your impending masterpiece. Ah, the humble click track; that annoying blippy-bloop that has become so much a staple of the music production process. Fun Fact: the first time I ever used a recording studio was when I was 17 — I booked a weekend to record 5 of my songs, playing all instruments myself — and the generic non-accented rimshot sound that the engineer dialled in to successfully penetrate my walloping snare drum is, to this day, my default click that I impose upon all my sessions when a click is deemed necessary. “Rimshot 2” it’s called. You can download it here, or listen to it here:

But the question is, “is a click track really necessary?” The short answer is “No”.

The longer answer is “Sometimes”.

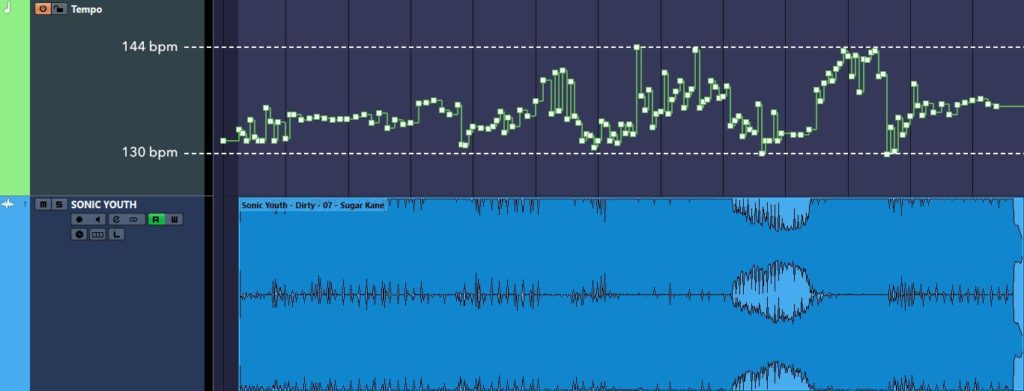

Let’s look at the short answer first. If a gigging band comes to my studio for a recording session, my impulse is not to foist a click track upon them as a starting point. It is always my intention to try and create as much of a natural environment for that band as possible, on the understanding that a band is fundamentally an ensemble unit, greater than the sum of its parts, and therefore as a whole has a unique character that is related to the dynamic interplay between its members. The tendency is to speed up during exciting bits, to slow down into the dreamy bits, and for members to cast glancing smiles at each other following the execution of the really cool bits — the click track sees all of these organic nuances as “errors” to be “corrected”; the tempo police castigating the band for enjoying themselves too much. I say, fuck that! That drum fill really was exciting! Don’t punish the chorus for it! All of my favourite albums from decades past were recorded without click tracks, and I don’t remember ever noticing or caring about any speeding up or slowing down. Here’s a view of a mapped tempo grid from the Sonic Youth song “Sugar Kane”, a 6-minute art rock masterpiece from 1992: