What Is Mastering?

Mastering recorded audio became its own discipline after the Second World War, when a “dubbing engineer”, secondary to the recording/mix engineer, was tasked with transferring the recorded audio from tape to a master disc, which served as the template from which all following vinyl discs would be pressed. This was a purely technical procedure, whereby the dubbing engineer’s job was to ensure that the final recording, which had been signed off by those creatively involved with the production of the music, was faithfully duplicated onto its designated medium.

Early vinyl records tended to be dogged by various inefficiencies in the tape-to-disc transfer process, not least that the dynamic range of the recorded material could be too large, resulting in the cutting of unplayable waveforms where the needle would actually pop out of the grooves, or even burning out the disc cutting head. The use of compressors and limiters in the mastering process became widespread in the 1960s, to cap the dynamic range at a particular threshold and thus ensure that such problems could be avoided. However, because this process was automated, often the dynamics processing employed was not sympathetic to the fidelity of the original material, and so over-compression would sometimes squeeze the life out of it, making everything sound consistently loud in a way that dishonoured the integrity of the original tape master. Some records ended up sounding particularly nasty due to this pitfall at the mastering stage.

And so, the solution to this problem?

Enter the mastering engineer.

By the 1970s, dedicated mastering studios had been established, staffed by sound engineers using high-end equipment. These “mastering engineers” were incredibly adept at finalising tape masters in an artistically satisfactory way, establishing mastering as a new artistic discipline that could actually make the final result sound “better” than the original recording.

Throughout the 80s and 90s, music production was revolutionised by digital technology, and CDs became the darling format of the music industry. To this end, the significance of mastering for vinyl became less prominent, as the problems incurred by analogue playback were no longer an issue in the digital domain. Mastering engineers, however, did not disappear, and instead their role migrated into audio specialists who serve as the last step in the production process – the guy or gal who collates all the final mixes for a particular release, and applies their technical wizardry to ensure that program volumes and tonal balancing are consistent throughout the entirety of the album. This is arguably of particular importance given the infinitely flexible DIY audio production world in which we now live, where track one may have been recorded and mixed in your bedroom, and track ten is a live recording from that gig you played last year – a far cry from the rigidly calibrated standards of professional audio recording of the 60s and 70s – the mastering engineer can be an invaluable specialist who coalesces all of these final mixes, “topping and tailing” each song to run seamlessly from one to the other, and thereby creating a pleasingly consistent album.

The Problem With Contemporary Approaches To Mastering

As we have seen, the discipline of mastering has migrated away from being a technical necessity, and has reinvented itself as an artistic process that seeks to “correct” and “improve” audio recordings. This is a fine line to tread, because one man’s improvement is another’s devastation. I have had this demonstrated to me quite painfully several times in years past, forcing me in those cases to temporarily conclude that mastering simply isn’t worth it, because a gung-ho engineer with itchy trigger fingers is too likely to ruin it for you.

In one such example, I finished working on two songs of my own, and rather than do what at the time was a normal process of finalising with some light compression, adding a little sweetening EQ and then normalising the result, I decided that it is high time I found myself a decent, trustworthy mastering engineer to whom I could reliably outsource my material to put the “finishing touches” on the mixes.

The result?

I was horrified – I thought it was a terrible detriment to my original mix; crushed with compression in a way that seemed horribly distasteful, and accompanied by notes claiming things like “I tried to make it a tad warmer and kill some spikiness in the guitar”. Slightly presumptuous, no? – Perhaps I like the spikiness in the guitar (I do). But of course, how was he to know otherwise? He is not familiar with my style, my artistic preferences, or what I consider important about my mixes, and so he was just trying to rectify the problems in the mix, as he perceived them. Attempts to articulate my preferences via email led to a cumbersome back and forth whereby words proved to be an inefficient medium in which to convey the subjective pleasure of ambiguous terms such as “guitar spikiness”. Moreover, given that I work hard to capture a wide, natural ambience in my music, especially in the drums, excessive limiting of transients in order to push up the aggregate volume of the music actually works against this kind of production style, and forces a kind of “breathlessness” in the music, where everything becomes squashed into a mulch of muddy sounding loudness.

Let’s take a closer look…

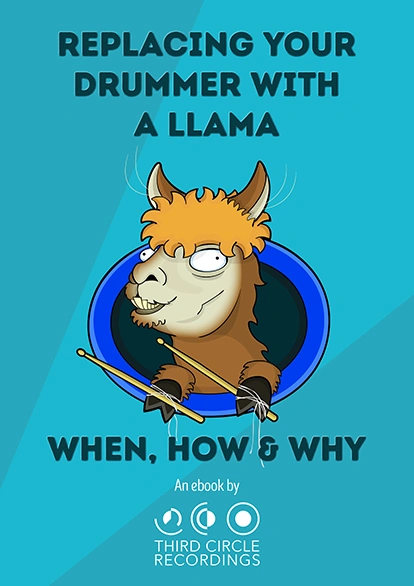

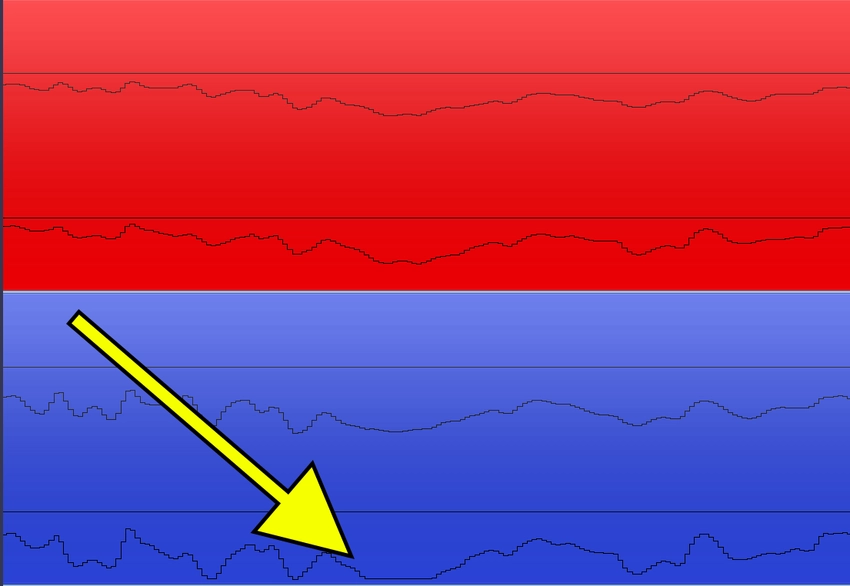

The image above depicts a stereo waveform representation of my original mix (red), followed by two subsequent masters from two different mastering engineers. In both cases we see that the audio peaks have been truncated in order that the aggregate level can be further maximised. The blue waveform represents an attempt by the first mastering engineer – this waveform is a real sausage! Obviously hugely compressed (oddly more so on the right hand side than the left), which manifests as very noticeable “gain pumping” (sharp volume rises and falls) when listening. Detailing this concern to the second mastering studio, they returned their master, which is the yellow waveform above. Noting that I was not a fan of excessive compression, they opted to still squash the mix, but just not as much. The result was a slightly less severe but still noticeable and ugly compression.

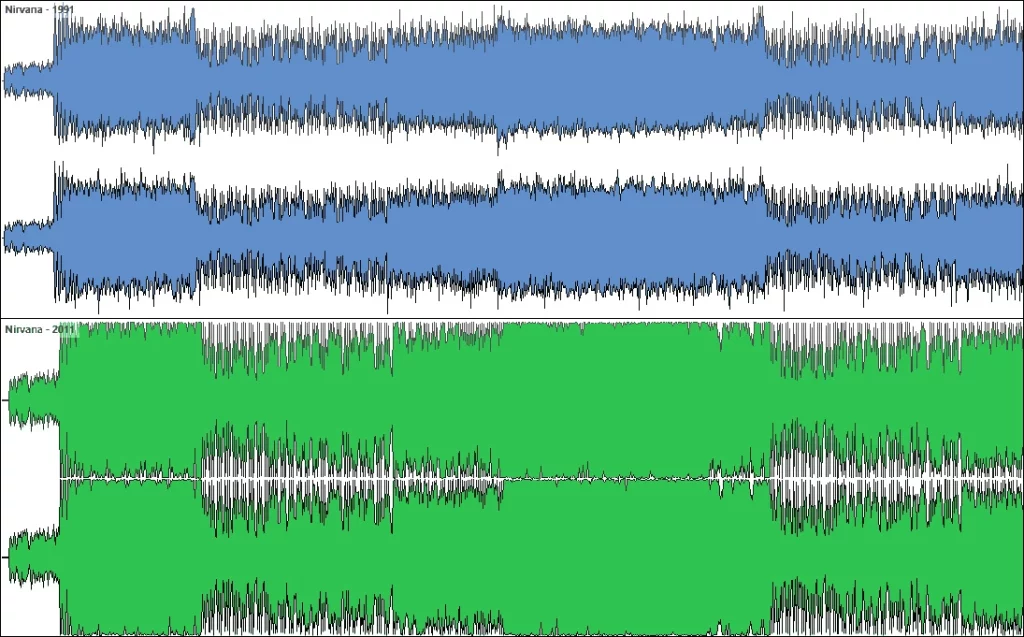

It actually seems to have become second nature to many mastering engineers to simply make everything as loud as possible, because, hey, louder = better, right? We can see this trend towards excessive loudness by comparing two more waveforms, this time from Nirvana’s song “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, recorded in 1991. The image below depicts the original 1991 master (blue), and the 20th anniversary remastered “Special Edition” from 2011 (green):

It is interesting to note that the blue waveform clearly shows Nirvana’s signature loud-quiet-loud song structure represented as an actual change in peak volume between the verses and the choruses. Cut to 2011 and this natural dynamic has been crushed in order to raise the aggregate level of the song, arguably sacrificing one of the very trademarks that made Nirvana such a dynamically versatile and intense band in the first place. So no, louder is not always better.

But here’s another reason to be wary of excessive compression. Look what happens when we truncate peak waveforms in this way:

The above image shows a close-up of my original mix (red) side by side with the first master (blue). What we see is that, by truncating audio transients we are actually sacrificing audio content that would otherwise have been present. The detail displayed in the red wave has been totally lopped off and replaced with something resembling a large square wave. Square waves actually introduce odd-ordered harmonics into the signal, which manifests to our ears as rather ugly distortion.

So it seems to me that we are somewhere close to the old days of ramming final mixes through limiters at the mastering stage simply as a matter of course rather than because the music actually warrants it. Indeed, when I suggested to subsequent mastering engineers that I don’t wish to overdo the compression, they still felt inclined to push it somewhat, rather than to err on the side of subtlety. It’s curious why this has become the norm, and of course the much discussed “Loudness War” of the 2000s has impacted significantly upon the industry, such that it seems as though a mastering engineer doesn’t feel he is creating value for money unless he is seen to be mastering for “competition volume”, or else tampering with the mix to some significant and obviously noticeable degree. But for me, this is not actually the job of a mastering engineer. It seems to me that a principled mastering engineer should not be afraid to listen to a mix and decide that nothing needed to be done to it. And to that end, their job is done, and they are still every bit as entitled to be paid as if they had actually decided that there were real tonal balance problems that needed to be rectified. The mastering engineer is your last line of defence against actual technical problems, not a dude who can make your mixes sound “shit hot”. Working under that preconception actually encourages sloppy mixing, because, hey, don’t worry – the mastering guy will fix it!

Should You Get Your Track Mastered?

In the right hands there is very often further creative mileage that can be explored from most recorded material after it has been mixed. There is certainly great value in having an objective pair of ears weigh in on mixes that were slaved over during intense and often time-limited recording and mix sessions. When the same material is worked on over and over again by the same people, some form of listen fatigue is fairly inevitable, such that even the most robust commitment to objectivity suffers under the psychological pressure of repeated exposure. The problem however – certainly in my experience – is that selecting an appropriate mastering engineer can be quite a challenge, as many are too trigger happy, their favourite plugins locked and loaded and ready to crush the life out of the material in favour of making it as loud as possible. My own experiences in mastering recordings has taught me the value of carefully making final corrections and enhancements to the overall mix, but the key word is careful. I am a fan of Ian Shepherd, who hosts an excellent podcast about mastering, which you can listen to here. This is a man who is principled in his approach, receptive to what the client wants and sensitive to the integrity and intent of the material. That is the correct way to be, and as I have mastered more and more material over the years, I have found that it is possible to tread that middle ground between improving the source material and respecting the clients’ intent.

Unfortunately I have witnessed many times mastering that has failed to align with the artistic vision of the source material. What’s worse is that the inexperienced ears of the band have often been unable to detect what may or may not be good about the end result, leaving them under the misapprehension that mastering is some kind of “black magic” process that is necessary but they’re not sure why. It is fairly easy to demonstrate the exact result of mastering by opening the mastered track in a DAW channel and aligning it alongside the original mix, bringing the volume of the mastered track down until it’s commensurate with the unmastered version and then flipping back and forth between them. This kind of experiment quickly reveals whether the mastered version has improved the sound or simply made it louder. It is something however that few bands will know to do instead just listening to the master in isolation, and therefore being more susceptible to the mastering engineer’s insistence that it sounds better now. To this end, mastering can really be a confusing quagmire for the uninitiated.

So. Should you get your stuff mastered? Very likely. But it is important to weigh it against your intentions for the material. Make sure whoever you choose is sympathetic to your vision and understands what you want to achieve, and likewise, make sure you understand what you hope to get at the end of it. And then, crucially, perform some tests – compare the mastered version to the original in the way I described, not just by listening to the mix and then the master, but by actively flipping between them in real time as the song is playing; this is the only reliable way to perceive what has actually changed in the two versions. This is very important, because too many out there think that the goal of mastering is simply to make it sound crushed to hell.